Summary: Many commentators have dismissed Matthew’s arrangement of his genealogy in groups of fourteen as sleight of hand. A more careful consideration of the matter, however, suggests Matthew’s arrangement is predicated on a close study of the Hebrew Bible. Key words: Matthew, genealogy, Jesus, Jehu, fourteens.

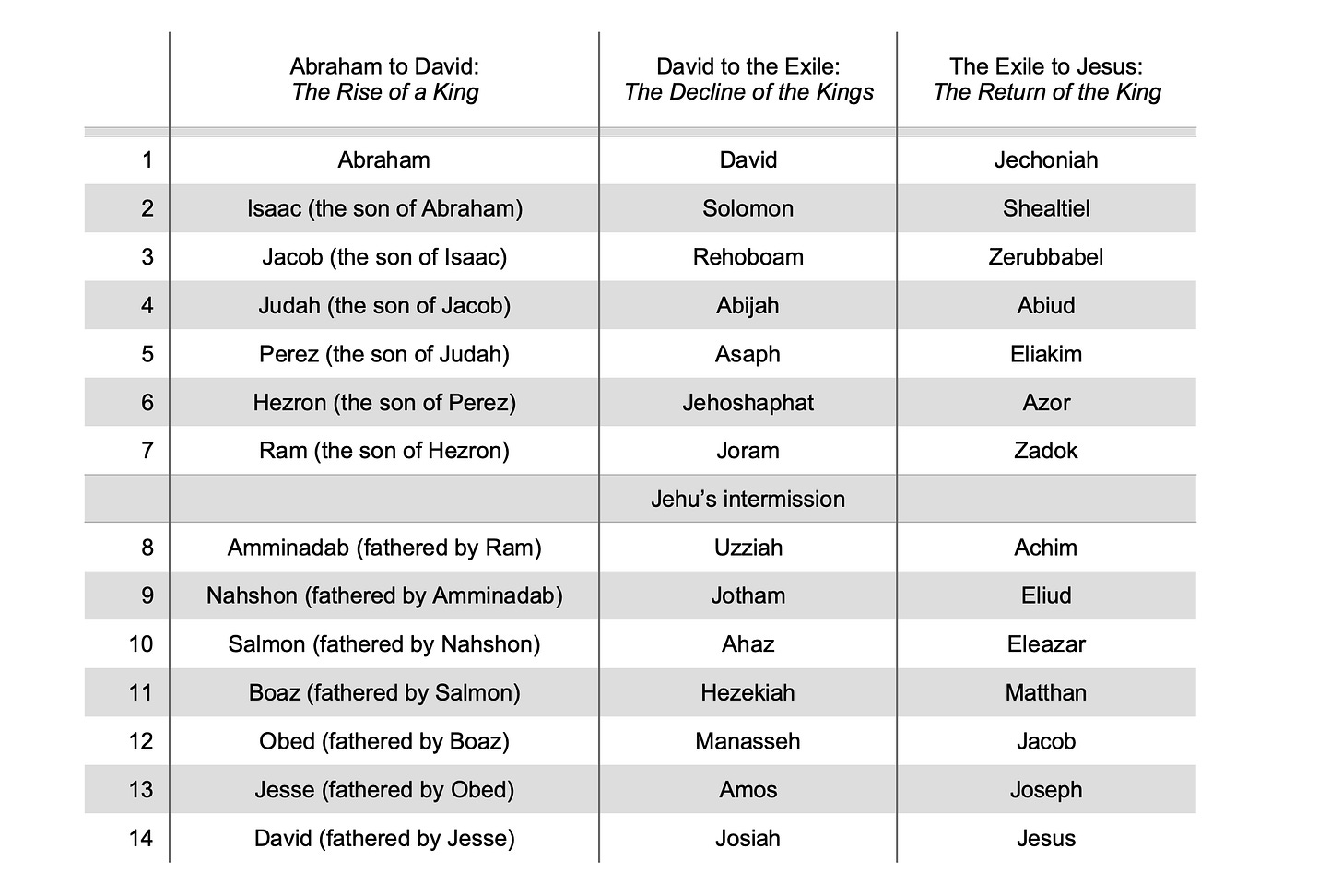

As is well known, Matthew’s genealogy (in Matt. 1.1–17) consists of three groups of fourteen generations. Between Abraham and Israel’s first great king (David) we have fourteen generations; between David and Israel’s great disaster (the exile) we have a further fourteen generations; and between the exile and Israel’s great deliverer (the Messiah) we have our final fourteen generations. Every fourteen generations, an event of epochal significance takes place, which makes Jesus’ arrival right on cue.1 ‘It’s almost as if God planned it’, Bart Ehrman says.

There’s a fly in the ointment, however, which is as follows. The interval between David and the exile isn’t actually spanned by fourteen kings; it’s spanned by seventeen kings. Matthew has bypassed three generations in order to make his pattern of fourteens add up.

Or at least so it seems. As Raymond Brown rightly points out, however, ‘It would be strange for Matthew to deliberately omit generations in order to create a pattern and then call his readers’ attention to it as if it’s some marvellous and (implicitly) providential pattern’. Brown therefore thinks Matthew must have stumbled across an ‘accidentally abbreviated’ list of Davidic kings and failed to realise it was three kings short. If we prefer, then, we can view Matthew as incompetent rather than disingenuous. But, before we jump to such conclusions, let’s take a step back and consider the bigger picture.

‘Jesus the Messiah, son of David, son of Abraham’

Matthew introduces us to Jesus as ‘the son of David’ and ‘the son of Abraham’ (1.1). These aren’t unrelated statements. When YHWH called Abraham, he said kings (מלכים) would emerge from Abraham’s loins (Gen. 17), and, with the emergence of David’s line, YHWH’s words began to be filled up.

Prior to David’s day, Israel had been led by isolated leaders: Moses, Joshua, the Judges, Samuel. Many of these men tried to establish dynasties (e.g., Judg. 10–12), but none succeeded. Then, in c. 1000 BC, a new era began. YHWH established ‘the throne of David over all Israel’ (2 Sam. 3.9–10) and said David would never be left without ‘a man on the throne of Israel’ (1 Kgs. 2.4) (if his sons walked faithfully before him)—a promise claimed by Solomon in 1 Kings 8.25 and 9.5. The term ‘throne of Israel’ thus has a specific sense in the Biblical narrative. It refers to the promise made to David, which was inherited first by Solomon and afterwards by the Davidic kings while the northern kingdom went its own way. (We’ll discuss an important exception to the rule later.)

If your sons, O David, pay close attention to their ways..., you will not be without a man on the throne of Israel (1 Kgs. 2.4).

YHWH has filled up his promise. And I, Solomon, have now risen in the place of David my father and sit on the throne of Israel (1 Kgs. 8.20 // 2 Chr. 6.10).

Now, therefore, O YHWH, God of Israel, keep for the sake of David your promise, when you said to him, ‘You will not lack a man to sit before me on the throne of Israel’ (1 Kgs. 9.5 // 2 Chr. 6.16).

Blessed be YHWH your God, O Solomon, who has delighted in you and set you on the throne of Israel! (1 Kgs. 10.9).

The throne-line defined by YHWH’s promise is clearly of great interest to Matthew, since his genealogy details its fulfilment. That’s why: a] when his genealogy reaches David, Matthew goes on to mention Solomon (and those who succeed him) rather than a different son of David (as Luke’s genealogy does), b] Matthew’s genealogy culminates in the fulfilment of a promise made to ‘the house of David’ to establish David’s ‘throne’ (cp. Isa. 7.14, 9.6 w. Matt. 1.23), c] Matthew’s genealogy leads into a narrative which tells us about the occupant of David’s throne at the time of Jesus’ birth, namely Herod (a man whose genealogy isn’t recorded by Matthew because he isn’t a son of David), and d] Matthew (uniquely) portrays the age to come as a day when the Son of Man will sit on his throne surrounded by the twelve, who are likewise seated on thrones (cp. 19.28).

To trace the course of the Davidic throne-line, however, isn’t a straightforward task due to the exception we mentioned earlier. Midway through the book of 2 Kings, we encounter two unusual references to ‘the throne of Israel’, which suggest it was (temporarily) removed from David’s line and entrusted to an outsider.2

In the 9th cent. BC, a king named Ahab enforced the worship of Baal in Israel with unprecedented fervour and forged close alliances with the house of Judah (aided by intermarriage between the houses of Ahab and David).3 The line of David thus came under threat. And so YHWH raised up a non-Judahite named Jehu to sort things out. YHWH made Jehu a remarkable promise: ‘Unto the fourth generation’, he said, ‘your sons will sit on the throne of Israel’ (2 Kgs. 10.30), i.e., on David’s throne. Which is exactly what happened. Hence, at the end of the reign of Jehu’s fourth son (Zechariah), the book of Kings’ narrator makes the comment,

The aforementioned events were [the fulfilment of] YHWH’s promise to Jehu. ‘Your sons will sit on the throne of Israel unto the fourth generation’, YHWH said. And so it came to pass.

Suffice it to say, then, the rise of Jehu’s dynasty represents a remarkable period in Israel’s history. YHWH handed the (already intertwined) lines of Ahab and David over to Jehu and commanded him to purge the influence of Baal from Israel (as well as avenge the blood of the prophets). And, in one of the most bloody eras in Israel’s history, Jehu obeyed. Jehu thus did what the Davidic kings should have done: he annihilated the house of Ahab, massacred the priests of Baal, and pulled down Baal’s temple, and in the process he removed Ahaziah from the throne, whose removal briefly brought Ahab’s daughter (Athaliah) to power.

Odd though the idea may seem, these events are highly relevant to our present enquiry. Why? Because Jehu and his descendants erased three kings from David’s throne-line. Jehu disposed of Ahaziah midway through his accession year, which means his name wouldn’t have appeared in official king lists,4 and Jehu’s descendants occupied David’s throne while Joash and Amaziah were in power (cp. the diagram below, which is derived from Young 2005). And these three kings (namely Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah) are precisely the three kings whom Matthew omits from his genealogy.

As Matthew tells us, then, only fourteen generations of David’s descendants sat on David’s throne (from Solomon to Jechoniah), which makes one for each lion on it (1 Kgs. 10.18–20).

That’s not, of course, to say Judah’s kings were ‘vassals’ of Jehu in any formal or political sense; it’s simply to say God no longer viewed David’s descendants as the occupants of David’s throne. He handed their authority over to Jehu, which created a lacuna in the Davidic throne-line; specifically, it split the second fourteen of Matthew’s genealogy into two groups of seven, which resonates with the way in which the Chronicler splits Matthew’s first genealogy into two groups of seven. (The Chronicler describes the first seven individuals as ‘sons’ of their fathers and the next seven as ‘fathers’ of their sons: cp. 1 Chr. 2.3–9 w. 10–15.)

The nature and significance of Jehu’s reign is reflected in the Biblical narrative in at least two further ways. First, in the Bible’s use of the term ‘the people of YHWH’. Jehu is said to be granted authority over ‘the people of YHWH’ (2 Kgs. 9.6), which is true of only two other individuals in Biblical history—Saul and David—, both of whom reigned over Israel as a whole (1 Sam. 10.1, 2 Sam. 6.21).

Second, in the Bible’s obituaries of Judah’s kings. At the end of each king’s reign, the books of Kings and Chronicles include a brief obituary, which is relatively formulaic in nature. Each king of Judah from Solomon through to Manasseh is said to ‘sleep with his fathers’ by means of a fixed phrase (וישכב דוד/שלמה/…עם אבותיו = ‘And PN slept with his fathers’), with three notable exceptions: Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah. And, like Jehoram, who married a daughter of Jezebel and hence sowed the seeds of Baal worship in Judah, all three of these kings are said to be buried in a separate location from the rest of the Davidic line, as shown below.

Note: The above pattern isn’t evident in Greek translations of the OT (or at least the ones in our possession today: cp. our Appendix), which suggests Matthew was more familiar with the Hebrew text of Scripture than is often assumed.

Apparently, then, like Matthew, the Chronicler takes the dynasty of Jehu to have disconnected David’s sons from their ancestry in some way. Perhaps, then, there’s method to Matthew’s madness after all. Indeed, even the specific number of generations bypassed by Matthew—i.e., three generations’ worth—seems significant in the wider context of Matthew’s Gospel. Matthew is known to arrange his material in groups of three (e.g., Davies & Allison 1988:62, Olmstead 2003:33), and his genealogy exhibits a number of threefold patterns and properties. Three Gentile women who wouldn’t have expected to have been included in the Messiah’s ancestry find themselves included in Matthew’s first group of fourteen, and a family of three (Joseph, Mary, and Jesus) unexpectedly appear at the head of Matthew’s third group of fourteen. (Their appearance is unexpected because Mary and Joseph haven’t yet consummated their marriage). That three Judahite men who would have expected to have been included in the Messiah’s ancestry are unexpectedly excluded from Matthew’s second group of fourteen thus has an ironic neatness. It also resonates with the three ‘clades’ of Israelites who are mentioned elsewhere in Matthew’s genealogy, yet whose lines are implicitly excluded (since they’re not pursued), namely those of Judah’s brothers, Zerah, and Jechoniah’s brothers. The Messiah descends from Judah rather than ‘his brothers’ (1.2), from Perez rather than Zerah (1.3), and from Jechoniah rather than ‘his brothers’ (1.11).

Note: Significantly, Glen Stassen has identified fourteen triads in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount (Stassen 2003), which makes it a neat complement to ch. 1’s genealogy, since, while Matthew’s sermon is built around fourteen groups of three, Matthew’s genealogy is built around three groups of fourteen.

By his omission of three particular kings, then, Matthew encourages us to view Jesus’ appearance in Israel against the backdrop of the reign of a very unusual ruler—Jehu—, which is unexpected yet serves an important purpose, since it highlights aspects of Jesus’ ministry we might otherwise overlook. Consider some of the similarities between Jesus and Jehu. Both men are unexpectedly anointed (to the amazement of those nearby). Both men’s reigns are announced in advance by an Elijah-like herald (or in Jehu’s case by Elijah himself). Both men claim to be driven by their zeal for YHWH (2 Kgs. 10.16, John 2.17). Both men have garments laid at their feet (by commoners) in acknowledgement of their kingship (cp. the triumphal entry). Both men would have been seen as illegitimate rulers by the majority of people in Judah, yet their reigns were explicitly sanctioned by God. And both men announce the downfall of a corrupt temple. These distinctly Jehu-like features of Jesus’ ministry emphasise the sense in which Jesus is a disrupter. His appearance in Israel signals a transfer of power; he comes to shake up the heavens and the earth (cp. Matt. 24.29–30); his death is accompanied by an earthquake (a detail unique to Matthew), which gives rise to new life in Israel (cp. God’s description of Jehu’s reign as an ‘earthquake’: 1 Kgs. 19.11–12 w. 15–17); and, a generation later, the Temple will fall and only those things which cannot be shaken will remain.

Final reflections

Matthew is not the careless or crafty compiler many scholars have taken him to be. ‘It would be strange’, Brown says, ‘for Matthew to have deliberately omitted generations in order to create a pattern and then to have called his readers’ attention to it as if it were some marvellous and (implicitly) providential pattern’. Brown is right. It would have been strange. Which is why Matthew didn’t do it. (Ehrman is closer to the mark when he says, ‘It’s almost as if God planned it’.) The actual course of events was as follows. God orchestrated the events of human history in accord with his divine plan; Matthew observed the signs of God’s handiwork in the Biblical narrative; Matthew reflected God’s handiwork in his account of Jesus’ genealogy; and we as readers are now able to discern it in Matthew’s genealogy. Matthew’s Gospel is thus an illustration of one of Jesus’ own doctrines: ‘Seek and you will find!’.

Appendix

How we’re supposed to count Matthew’s lists of names isn’t immediately apparent. Matthew tells us there are fourteen generations from ‘Abraham to David’, fourteen from ‘David to the exile’, and fourteen from ‘the exile to the Messiah’ (1.17). We’re clearly, therefore, supposed to double-count David (since Matthew’s generations run from ‘Abraham to David’ and then from ‘David to the exile’). But what about Jehoiachin? Insofar as Jehoiachin survived the exile, he could theoretically be included in the generations from ‘David to the exile’ or in the generations from ‘the exile to the Messiah’ or both. Which, then, should we choose? Well, since Matthew’s second and third groups of fourteen are demarcated by the exile—that is to say, since Matthew doesn’t tell us we have fourteen generations from ‘David to Jehoiachin’ and ‘Jehoiachin to the Messiah’—, we probably shouldn’t double-count Jehoiachin. We therefore have to assign Jehoiachin to one side of the exile or the other. And, if we assign him to the far side of the exile, Matthew’s count of fourteen adds up, which suggests it’s how Matthew has arrived at his stated counts.

As Leithart notes in his commentary on Kings (with no particular point to prove as far as Matthew’s genealogy is concerned), ‘When judgment falls on Ahab’s house, it engulfs David’s as well’ (Leithart 2006:223).

The northern and southern kingdoms had become—to borrow an image from Ezekiel—twin prostitutes (Ezek. 23). Judah was merely a mirror of Samaria, as is reflected in the overlap in their kings’ names. The two kingdoms had become indistinguishable (Leithart 2006:232). A radical ‘reboot’ was therefore needed.

King lists tend to measure reigns in complete years—or, to put the point another way, king lists tend to assign years to one and only one king. Typically, then, a king who doesn’t complete his accession year won’t appear in official lists. For an analysis of the relevant dates and accession methods, cp. Young 2005 esp. 246.

Really good piece of work.

There is one detail that does not seem apparent to me though - your mention that Amaziah was 'buried in a separate location from the rest of the Davidic line' and 'buried in a separate location from the rest of the Davidic line'.

2Kings14:20 NKJV seems to imply otherwise in saying that Amaziah 'was buried at Jerusalem with his fathers in the City of David' and that he 'rested/slept with his fathers' (vs 22, which according to the BSB refers to Amaziah rather than his son Ahaziah). Is there some textual/translation issue behind your comments here?

Regarding the comment that Matthew seems to have a lot of 3's going on, another one (implicit) is 3 x 7=21 generations from Adam to Abraham (as per Luke 3, following the LXX inclusion of 2nd Kainan). Though perhaps it could be said that there are still 3x7 generations to Abraham in the MT text if beginning with God (Lk 3:38) rather than Adam.

See Smith & Udd (2019) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-685AsaGuXVgFENpMH0FNUL23_pwCRfm/view