Summary: The book of Judges is built around a series of inversions/travesties of Israel’s three main feasts. These ‘feasts’ are not memorials of God’s goodness; rather, they are a liturgy of violence. Israel forget what they should have remembered and unintentionally memorialise what they should never have done in the first place. Key words: feasts, Judges, narratives, literary analysis, exegesis. Date: May 2021.1

The book of Judges is a book of deliverance. That might make it sound like a fairly upbeat story. Sadly, however, it’s anything but. As the book unfolds, its acts of deliverance become progressively more grisly and paradoxical, as do its deliverers, until, in the book’s awful finale, deliverance never comes; a helpless woman is delivered over to her enemies. These acts of deliverance--or, in the last case, non-deliverance--are portrayed as inversions/antitheses of Israel’s major feasts.

Gideon’s anti-Sukkot

Things start to go wrong pretty early on in the book. Like Saul, Gideon begins his career with impressive humility (cp. 6.15 w. 1 Sam. 9.21). But before too long--again like Saul--, Gideon turns brutal.

His brutality is framed against the backdrop of the feast of Tabernacles.

Under normal circumstances, the feast of Tabernacles (aka ‘Sukkot’ = ‘booths’) is celebrated on the 15th of Tishri, towards the end of the grape harvest. The Israelites head to the hills, from where they gather fruits and branches, and afterwards they return to their houses, build booths (often on their roofs), and sleep under the starry sky (cp. Lev. 23.40–43, Deut. 16.13, Neh. 8.14–18).

In Gideon’s case, however, the feast is reinvented, and not for the better.

As his judgeship begins to degenerate into a quest for vengeance (cp. 8.19), Gideon has two kings beheaded in a ‘winepress’ and refers to his slaughter of the Midianites as ‘a grape harvest’ (8.2). And, as the 15th day begins to dawn in the book of Judges--i.e., as the word ‘day’ occurs for the 15th time--, Gideon visits the town of ‘Sukkot’ (8.5, 8.28). Rather than fetch branches from the hillside, Gideon fetches briars from the wilderness and flays the elders of Sukkot with them (8.16).

Gideon’s reinvention of the feast of Tabernacles leaves a permanent impression on Israel. In chapter 9, Gideon’s son (Abimelech) continues the violence his father has begun, which has equally Sukkot-like overtones. Just as seventy bulls are sacrificed at the feast of Tabernacles (i.e., 13 + 12 + 11 + 10 + 9 + 8 + 7: cp. Num. 29.12–34), so Abimelech sacrifices Gideon’s seventy sons (on a single stone) and proclaims himself claim king of Shechem. And, just as the feast of Tabernacles is set against the backdrop of the olive, fig, and vine trees’ produce, so too is Abimelech’s reign (courtesy of Jotham’s parable) (cp. Deut. 11.14, 15.12–14 w. 1–11, 16.13).

Once Abimelech (the thorn-king) has been ‘enthroned’ in Shechem, things get even more bloody. The time of the grape harvest soon comes round, at which point a festival is in progress; and, right on cue, the festival turns sour (9.27ff.). The resultant events revolve around a sequence of Sukkot-like activities in reverse order. Abimelech launches an attack against the men of Shechem. (He’s spent the previous night under the starry sky.) The men of Shechem flee for safety to the roof of a nearby tower (9.46). And, in response, Abimelech and his men head to the hills to fetch brushwood (cp. soko w. Sukkot !), which they pile up next to the men of Shechem’s tower (9.48–49). Suffice it to say, Abimelech and his men’s desire isn’t to build a booth; it’s to roast the men of Shechem alive, which they soon manage to do. The text of ch. 9 thus moves backwards through the events of a normal Sukkot in order to reflect Abimelech’s inversion/perversion of YHWH’s appointed feast. The fertility and greenery of Canaan is turned to violent ends; the Israelites look to establish a kingship rather than to remember their sojourn; and blood flows rather than wine.

Jephthah’s anti-Passover

The book of Judge’s next flawed deliverer is Jephthah. As the Ammonites close in on Gilead, the Gileadites decide they need an experienced warrior to bail them out of trouble. They thus hire Jephthah. And, initially, their decision bears fruit. Jephthah accomplishes a distinctly Passover-like deliverance. Just as the angel of death passes through (עבר) the land of Egypt and smites the land and its gods, so Jephthah ‘passes through Gilead’ (עבר) into Ammon (עבר again), where he smites the Ammonites and their god (cp. 11.21–25, 32 w. Exod. 12.12ff.). And, just as Moses’s sister comes to meet him with ‘timbrels and dances’ in the aftermath of Egypt’s defeat, so too, in the aftermath of Ammon’s, Jephthah’s daughter comes to meet him (11.34 w. Exod. 15.20).

Jephthah’s judgeship thus gets off to an extraordinary start. Yet, even as Jephthah’s daughter comes to celebrate Israel’s victory, Jephthah’s Passover deliverance starts to devolve into an anti-Passover. Jephthah has made a foolish vow. And, whereas YHWH’s fulfilment of his Passover vow results in the salvation of his firstborn (Israel), whom he brings up (להעלות) out of Egypt (Exod. 3.17, 6.8, etc.), Jephthah’s results in the death of his firstborn, whom he’s forced to sacrifice (להעלות) on the altar of his folly.

Other anti-Passover traits aren’t hard to identify. While Moses’s Israelites escape through a body of water in the aftermath of the Passover, Jephthah takes control of the fords of the Jordan and prevents the escape of 42,000 Israelites (12.5). While Israel arrives at Mount Sinai two months after the Passover, where she enters into a covenant with her God (cp. Exod. 19, Jer. 2), Jephthah’s daughter heads into the mountains for two months to lament her singleness.2 And, while YHWH’s Passover becomes established as a statute (חֹק) associated with Israel’s preservation, Jephthah’s becomes part of a ‘custom’ (חֹק) associated with the end of his line (cp. 11.39 w. Exod. 12.24). Jephthah’s legacy in Israel is a legacy of death.

The ‘deliverance’ effected by Jephthah thus comes at a high price. What should have been remembered as a victory becomes part of the book’s liturgy of violence. And, viewed in light of the Akedah (Gen. 22), its horror becomes even more apparent. Whereas Abraham is commanded to sacrifice his only son (יחיד), who is delivered from death at the last moment, Jephthah decides to sacrifice his only daughter (יחידה) on his own initiative, and deliverance never comes. Heaven remains silent, as we hear YHWH’s last statement to Israel ring out clearly in the background: ‘I will deliver you no more’ (10.13).

Samson’s anti-Pentecost

Our next flawed deliverer is Samson, who enacts an anti-Pentecost. Before we consider Samson’s activities, however, let’s briefly remind ourselves of the New Testament’s Pentecost. In Acts 1–2, a remarkable sequence of events unfolds: Jesus is taken up into the heavenly realms; the time of the wheat harvest comes; the Spirit rushes on the apostles like a mighty wind; fire falls from the heavens; and, as the last forty years of Israel’s biblically-attested history begin, 3,000 men are miraculously saved.

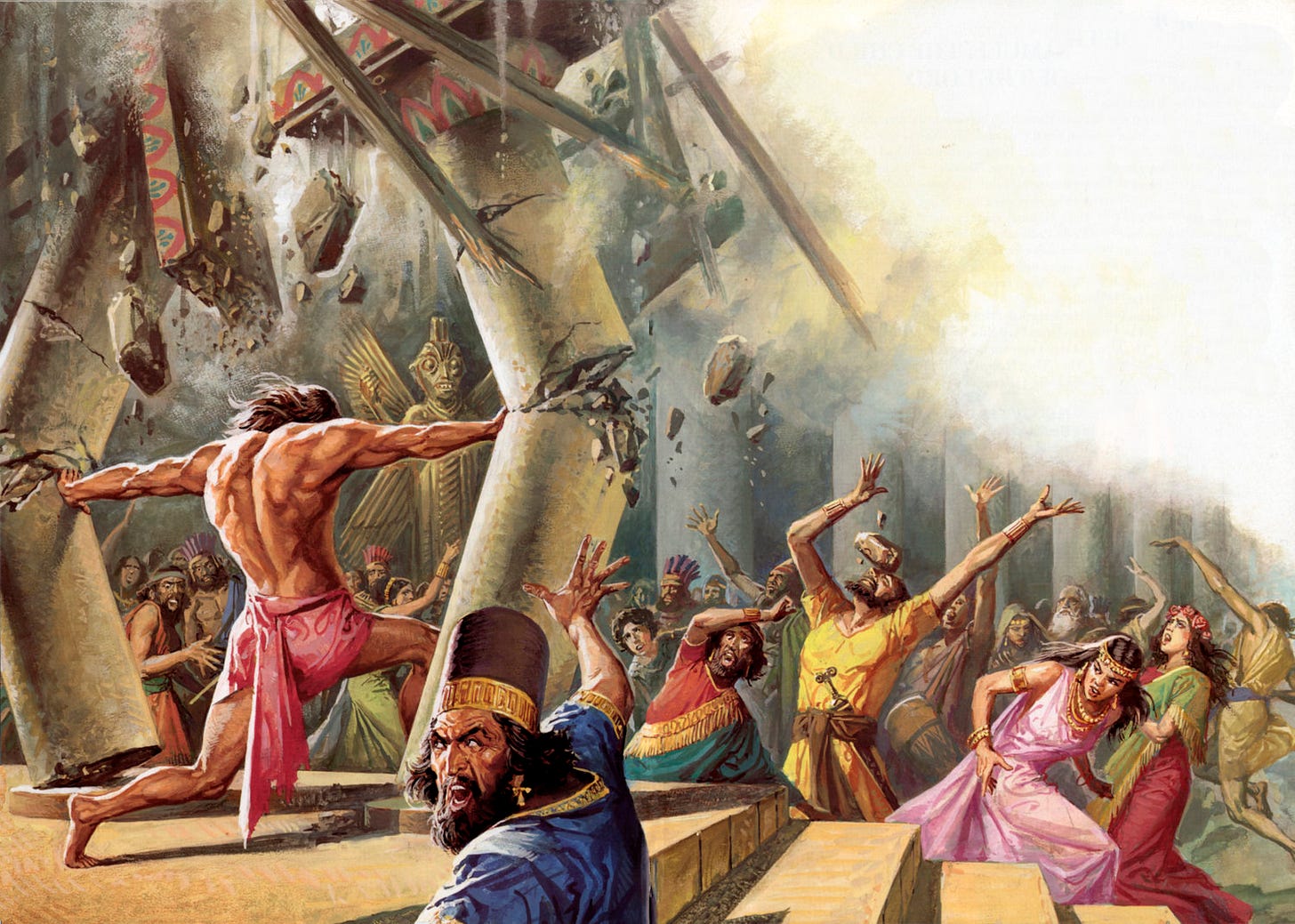

In the Samson story, what looks to be a similar sequence of events begins to unfold. A man of God (with a ‘wonderful name’) ascends into the heavenly realms (13.18–20); the Spirit rushes on Samson (14.6); and, afterwards, the time of the wheat harvest comes (15.1). True to Samson’s character, however, Samson’s Pentecost soon takes a brutal turn. In contrast to what follows the Spirit and fire of Acts 2, an attempt to take a Gentile bride ends in disaster (15.2). The Spirit-filled Samson sends fire against the Philistines, who return the compliment (15.4–6). Rather than save 3,000 Israelites, Samson slays 3,000 drunken Philistines (drunk with wine rather than the Spirit). And, as the last forty years of the Judges’ history draws to a close (cp. 13.1), a great temple falls (16.27–31), as it does in AD 70.

The Levite’s anti-Passover

We thus come to the book of Judges’s final anti-feast: the Levite and his concubine’s night in Gibeah (chs. 19–21). Our author has saved the worst for last.

Ch. 21’s events are traditionally dated to Av, the fifth month of the year (b. Ta‘anit 30b). If the relevant tradition is accurate, ch. 19’s events would have taken place in Nisan (cp. 20.47). Either way, they begin in Passover-esque fashion. We have a group of people in a foreign land equipped with plenty of straw, a host who repeatedly says he’ll let the people go (only to change his mind nearer the time), and, finally, a meal eaten within the safety of a house at night while terror lurks outside the door (cp. 19.1, 5–10, 16–19 w. Exod. 12.22–23).

As the relevant night draws on, however, the Levite and his concubine’s story starts to morph into an anti-Passover. The terror outside the door is not the terror associated with a holy God. And, whereas YHWH leads (הוציא) his people out of Egypt and rescues them from danger (Exod. 12.42), the Levite casts (הוציא) his concubine into the outer darkness in order to save his own skin. The woman is hence abandoned to face the terrors of the night alone, where, like the men of Laish before her, she finds herself ‘without a deliver’ (אין מציל) (cp. 18.28) as we again hear the words ‘I will deliver you no more’ ring out. Indeed, God is not the subject of a single verb in Judges 19. Per Romans 1, he hands Gibeah over to its own desires, and the events of Judges 19 are the result. Not until dawn breaks do the men of Gibeah ‘release’ the concubine (the verb ‘release’ [לְשַׁלַּח] is the central verb of the exodus narrative), by which time, in a cruel travesty of Exodus 12.10’s stipulation, little of the woman’s life is left. (‘Let none of it be left over the next day’: cp. 19.25.) The Levite thus arises to find blood on his doorposts, at which point, to the reader’s horror, things get worse. While Pharaoh’s command ‘Arise!’ (Kumu!) finds its answer in the exodus, the Levite’s equivalent (Kumi!) goes unanswered. And then, in a final anti-Passover moment, the Levite cuts his victim up ‘into bones’ (לעצמים). (‘Not a bone of the lamb is to be broken’.)

The book of Judges’ anti-feasts thereby reach their climax in one of the most brutal and horrific scenes in all of Scripture, which is an apt summary of the book’s portrayal of Israel--a people who have forgotten what they should remembered and unintentionally memorialised what they should never have done.

Note: The Bible is often said to treat Israel’s feasts inconsistently, which has led to the development of an array of source-critical theories over the years. (While Leviticus knows of all seven feasts, the book of Judges is only said to know of one otherwise unattested feast at Shiloh and another at Gilead.) If the claims of the present note are correct, however, then the book of Judges is only too well aware of Israel’s feasts, and its narrative has been crafted precisely in order to reflect Israel’s corruption of them. That the book of Judges doesn’t make explicit mention of any feasts doesn’t, therefore, reflect inconsistency on the behalf of the Biblical text, but on the behalf of Israel’s religious practice.

A final reflection

Suffice it to say, the book of Judges isn’t written to glamorise Israel’s history; it’s intended to shock and disturb its readers--to reflect the depths of man’s inhumanity, to preserve the voice of Israel’s victims, and to document the consequences of departure from the one true God.

Thankfully, however, Judges 21 doesn’t mark the end of the Biblical narrative. In the NT, in the person of Jesus Christ, God himself enters into man’s fallen history. He becomes the hero to the book of Judges’ male anti-heroes and the Messiah who shares in the pain of the book’s female victims. He doesn’t respond to violence with violence (as Gideon and Samson do), nor does he desire power and dominion (as Abimelech and Jephthah do). Instead, like Jephthah’s daughter, he surrenders his life so a father’s promise might not be broken. Or, to put the point in terms of Judges 19, he does what the Levite should have done yet failed to do: he steps out into the darkness and hands himself over to his enemies (cp. ‘If it is me you seek, let these men go!’) so others might be spared. In Christ, life’s circle/liturgy of violence can be broken. And one day it will.

Image sourced from KnowingScripture.com

Also worthy of note in terms of the connections between Sinai and Jephthah’s daughter is her unusual statement, ‘I will descend upon the mountains’ (וירדתי על ההרים), which establishes a verbal connection with the events at Sinai where YHWH is said to ‘descend upon the mountain’ (וירד על ההר) (cp. 11.37 w. Exod. 19.20).

Mind Blown!

This excellent, James. Thank you...