Parables, Prodigals, & Parallels to Purim

What do Jesus’ sermon in Luke 15–16 and Purim have in common? In a nutshell, they both revolve around feasts and reversals. For the details, please read on.

Jesus’ sermon in Luke 15–16 involves a series of five parables:1

the lost sheep,

the lost coin,

the lost son(s),

the lost steward, and

the rich man and Lazarus.

Each parable climaxes in an important reversal of fortunes, as does Luke’s Gospel as a whole (in Jesus’ resurrection). The lost sheep, coin, and son are found. The lost steward secures a future for himself. And Lazarus’s misfortunes in life are compensated in the afterlife. Most people love to hear stories like these. But why? The shepherd doesn’t end up any with any more sheep than he started with, and the same can be said (mutatis mutandis) for the woman and the father. So why do these stories appeal to us? Is it just a quirk of the human psyche?

I don’t think so. We’re made in the image of a God who loves to restore--a God of Jubilees, a Shepherd whose delight is to seek and save the lost (Ezek. 34.11–16, Luke 4.18). As a result, lost-and-found stories have an appeal to us. Who doesn’t rejoice when they find what they’ve lost? Or, to paraphrase the first parable, what kind of shepherd wouldn’t rejoice when he’d found his lost sheep? Well, we’ll soon meet one (in the parable of the lost sons). But first let’s think a bit more about feasts and celebrations.

Jesus’ five parables involve a number of feasts/celebrations. When the lost sheep is found, the shepherd celebrates, as does the woman who finds the lost coin. When his son is found, the father throws a banquet. And the rich man is clearly no stranger to feasts (and doesn’t seem to need a reason to have one). Feasts also occur elsewhere in Luke. The book is full of them, and culminates in one (e.g., 14.8ff., 22.1ff.). Yet Luke isn’t the only book to involve lots of feasts. A well-known OT book also does so--the book of Esther. The king has a feast. The queen has a feast. Esther has a feast organised for her (and organises two of her own). And, at the climax of the book, the Jewish people inaugurate a yearly feast, which they still observe today.

Esther also involves a number of reversals, just as Jesus’ parables do. For a start, its finale constitutes a reversal of the state of affairs described at the close of the book of Lamentations, which follows on from it in Tiberian manuscripts.

At the end of Lamentations, the land of Israel is ‘turned over’ (הפ׳׳ך) to foreigners and the Israelites are left orphaned (5.2–3); then, at the outset of the book of Esther, we meet a young orphan (Esther!) who reverses (הפ׳׳ך) the Jews’ fortunes and causes foreigners to assist their cause (8.17, 9.1, 3). At the end of Lamentations, Israel’s princes are hung from trees (5.12) and relieved of their crowns (5.16), while in Esther Israel’s enemies are hung from trees and Mordecai is awarded a crown (by the king of Persia). And, at the end of Lamentations, Israel’s joy (שׂו׳׳שׂ) turns (הפ׳׳ך) to sorrow (אבל), while at the end of Esther Israel’s sorrow (אבל) turns (הפ׳׳ך) to joy (שׂו׳׳שׂ) (cp. Lam. 5.15, Est. 8.16, 9.22).

Note: In modern Hebrew, the word for ‘a latte’ is based on the verb ‘to reverse’ (הפ׳׳ך) since it consists of milk with coffee in the top rather than the other way round (coffee with milk in the top). Before anyone asks, though, the name Keren Happuch (קרן הפוך) probably shouldn’t be translated as ‘a flask of coffee’.

The book of Esther thus describes a reversal of Israel’s fortunes, which answers the final plea of Lamentations: ‘Restore us, O YHWH, and renew us as of old!’ (5.21). Moreover, Esther’s reversal of fortunes involves a whole series of mini-reversals. The man who wanted to be paraded around on horseback (Haman) has to parade his rival through the city square on horseback (to the cheers of assembled multitudes). The letters with which Haman decreed the destruction of the Jews are used to decree the death of Haman’s sons (while Haman hangs from his own gallows). And, on the day when the Jews’ enemies plan to blot them out of Persia’s chronicles, the Jews instead blot out the memory of Amalek (Exod. 17.14) and have remembered their victory ever since.

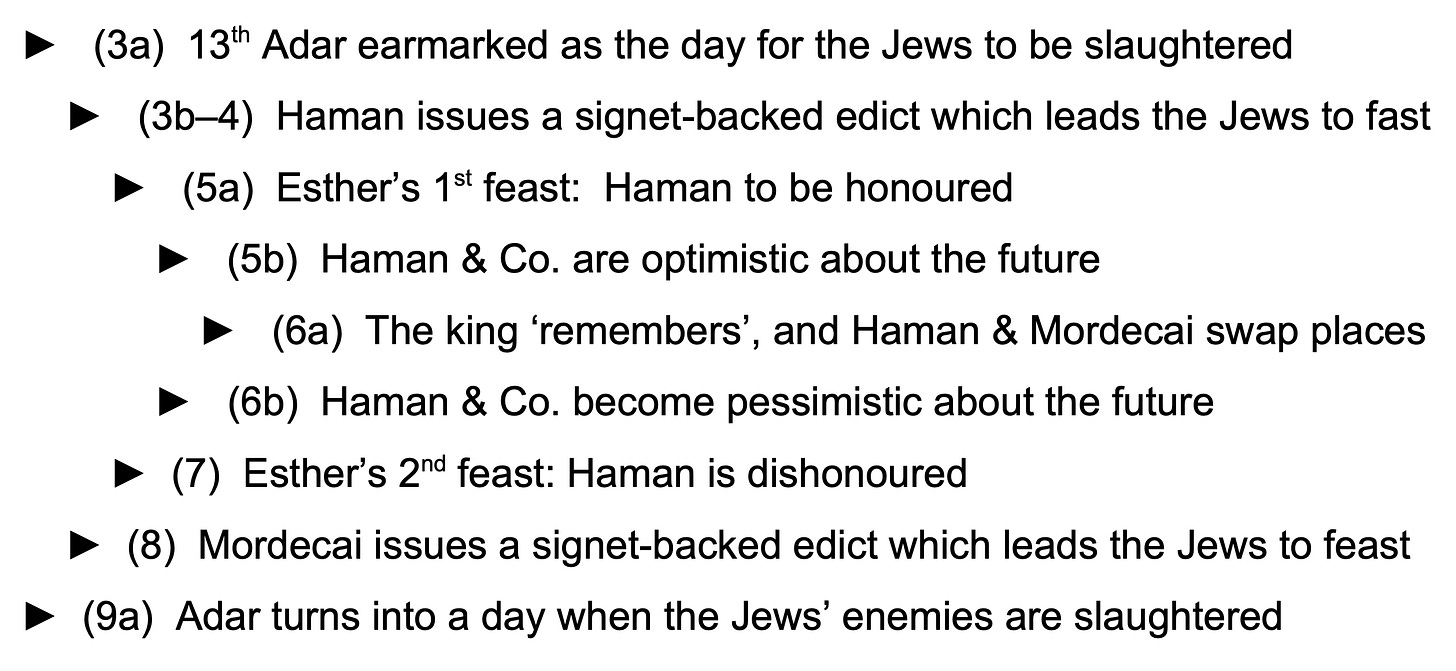

Summaries of the book of Esther thus abound with chiasms. Some of them even seem quite plausible. Here’s one of my efforts:2

But what do all these considerations have to do with Luke 15–16? Well, for a start, they shed significant light on the older brothers’ situation in Luke’s central parable (15.11–32). Recall the experiences of Haman at the midpoint of the book of Esther (chs. 5–7).

Haman has finally rid himself of those pesky Jews--or so he thinks--when Mordecai emerges from the woodwork and spoils his fun. The most decorated man in the kingdom he may be, yet Haman is unable to enjoy the queen’s feast for a moment until he has been acknowledged as Mordecai’s superior (5.9–14). Haman thus goes home and plans out how he’ll dispose of Mordecai and how he’ll celebrate once he’s done so, which makes him feel better. (There’s nothing like the prospect of murder to lift the spirits, right?)

The next day, however, Haman gets a surprise. He’s told the king wants to bestow a great honour on someone, which he naturally assumes means him. After all, who else could the king possibly want to honour? It turns out, however, that the king does want to honour someone else, and that the ‘someone’ in question is none other than Mordecai--the man he’d deemed as good as dead! The robes he should have worn are to be given to a man who doesn’t even obey the laws of the land (3.8), and the fame and recognition he deserves is to be enjoyed by a Jew! Worse still, Haman is expected to parade Mordecai through the city square on horseback and to rejoice in Mordecai’s exaltation!!

The parallels between the experiences of Haman and those of the older brother (in Luke’s parable) aren’t hard to see. They are framed within a different context, of course, but their essence remains the same. The older brother has little love for his younger brother. While the shepherd in the first parable heads off in search of his lost sheep, the older brother does nothing at all to find his lost brother. And why should he? His brother has shown no respect for the laws of the land (or for his father) (15.12). The older brother doesn’t even seem that displeased by his younger brother’s disappearance, since what’s left of his father’s estate is now his alone to enjoy. Or so he thinks. Suddenly, however, like Haman, the older brother gets a surprise. His long-lost brother returns, and his father gives his brother what should have been reserved for him: the robes, the recognition, the fatted calf, the whole works. Worse still, his father expects him to be happy about it--which, like Haman, he is unable to do.

The connection between Jesus’ parable and Esther is underlined in more specific ways. Just as the father’s commands his servants ‘Quick, get the best robe!’, so the king commands Haman ‘Quick, get the royal robe!’ (Est. 6.10, Luke 15.22). And, just as Mordecai ultimately receives not only a robe but a ring, so too does the younger brother.

So, how might Jesus’ parable have gone down with its audience?

Well, many of the Pharisees and scribes would no doubt have realised its significance (cp. 16.14): the older brother wasn’t an incidental character added to make the plot work; he was a depiction of them, the Pharisees and scribes. Like the older brother, the Pharisees had no love for Israel’s lost ‘sinners’. They’d only just been grumbling about Jesus’ engagement with such folk (15.2), and not for the first time (5.30, 7.34, 39). To put the point in Ezekiel’s terms, the Pharisees had no time for the lost or the lame; they’d entered the shepherd business for what they could get out of it: fat and wool (Ezek. 34.3ff., Luke 16.14). That was why it had been necessary for YHWH to send another shepherd--a Good Shepherd--, which YHWH did in fulfilment of his declaration to Ezekiel:

‘Since my shepherds have not gone to search for my lost sheep,...I myself will seek them out’ (Ezek. 34.8ff. w. Luke 19.10).

The Pharisees would thus have felt decidedly uncomfortable as they listened to Jesus’ parable. At first, they’d probably have been quite happy to be identified with the older brother: the younger brother had wandered astray, while the older brother, like them, had remained steadfast. They wouldn’t, however, have been so happy when the older brother’s situation took a rather Haman-esque turn. And they wouldn’t have liked the text’s other allusions either. The older brother’s actions don’t only resemble those of Haman; they also resemble those of Esau--Haman’s ancestor (Gen. 36.12, 1 Sam. 15.8)--, who comes in from the field one day to find half his inheritance gone, just as the older brother does (Gen. 27.30, Deut. 21.17). Were the Pharisees about to lose their inheritance too?

Either way, they had a difficult decision to make: to identify with the sinners who’d wandered away from God or to identify with God’s enemies. And things weren’t about to get any easier for the them, as we’ll now see.

Back to the Parables

Recall Luke 15–16’s series of parables:

the lost sheep,

the lost coin,

the lost son(s),

the lost steward, and

the rich man and Lazarus.

As we’ve noted, all five parables involve a reversal (the sheep is found, the son is welcomed back, etc.). As the series unfolds, however, the reversals become more complex. When the lost sheep is found, it rejoins the rest of the flock. And, when the lost coin is found, it’s put back with the rest of the coins. All well and good, one might say. Yet, when the lost son returns, life becomes a lot more awkward for his brother. When the lost steward shores up his future, he does so at the expense of his master’s business. And, when Lazarus’s misfortunes in life are recompensed, the rich man is judged for his unfaithfulness.

These reversals reflect the imagery employed elsewhere in Luke and related texts. God won’t just satisfy the hungry; he’ll also send the rich away empty-handed (1.52ff., 6.24ff.). God won’t just raise up the valleys; he’ll also flatten the mountains (3.5, 14.11, 18.14). And God won’t just restore the sheep who’ve gone astray; he’ll also destroy the (fat and stubborn) shepherds who’ve let them do so (Ezek. 34.16).

Jesus’ final parable thus reveals the seriousness of the Pharisees’ plight. At the end of the third parable, the older brother’s final state isn’t described, since the Pharisees’ final state isn’t yet decided. It depends on how they respond to Jesus’ challenge. Jesus’ fifth parable then picks up where his third parable left off: it reveals what the consequences of the Pharisees’ inaction will be. If the older brother won’t rejoice with his father (Abraham) in the present life, then he won’t rejoice with Abraham in the afterlife either. The poor will be welcomed into the presence of Abraham, while the Pharisees will be shut out (14.21–24).

Also important to note is the way in which Jesus’ fifth parable picks up on his third parable’s allusions to Esther. It begins with a rich man clothed in purple and fine linen who feasts on a daily basis. Jesus’ choice of imagery is significant. The rich man is Haman--a man whose loyalties lie with Persia, who delights in the kingdom’s purple and fine linen, and who feasts with Persia’s VIPs on a daily basis (Est. 1.3–6). Moreover, there’s a Jewish man at the gate (Lazarus) who corresponds to the Jewish man at the gate in the book of Esther (Est. 4.1ff.). While the rich man feasts in his house, Lazarus lies at his gate in pain, and, similarly, while Haman feasts in the palace, Mordecai lies at the palace gate and mourns (Est. 3.14ff., 4.3).

Another significant detail of Jesus’ parable is its order of events. Unlike its predecessors, Jesus’ final parable doesn’t end with a feast; it begins with one. Why? Because, like Haman, the rich man has enjoyed his good things in life, and will not experience good things in the afterlife. (‘Woe to you who are rich for you have received your consolation, and woe to you who are full now, for you shall be hungry!’) The rich man will instead find his and Lazarus’s fortunes reversed: specifically, he will find Lazarus seated at the master of the feast’s right hand (just as Mordecai is in Esther), while he, like Haman, is on the wrong side of the king and is able only to beg for mercy.

Jesus’ fifth parable is thus intended to warn the Pharisees of the future which awaits them unless they radically change their ways. Their lives are like the life of the rich man. They are far more concerned about their riches than about the poor (16.14), and are no strangers to feasts, fine robes, and VIPs (20.46). As John warned them, however, the axe is at their roots, and the mere confession ‘Abraham is our father’ will not save them from the flames (3.8–9), which the rich man’s unanswered cry illustrates (‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me...!’: 16.24–25).

Jesus’ parable is thus a call to repentance--a call for the Pharisees to live as true children of Abraham and to recognise the Lazaruses of the world as their brethren. The rich man, however, has a different family on his mind. He’s not worried about the unfed Lazaruses in Israel; he’s worried about the five brothers in his father’s house.

Who are these five brothers? Well, in Jesus’ day, the high priest was a man of significant wealth named Caiaphas, and Caiaphas is known to have had five brothers-in-law (who later served as high priests). Furthermore, like the rich man in the parable, Caiaphas would often have been clothed in purple and linen (cp. Exod. 28). It doesn’t, therefore, seem implausible to take the rich man’s five brothers to refer to Caiaphas’s brothers and hence to subsequent high priests--men who remained unresponsive to Jesus’ message even after (per the rich man’s suggestion) someone did in fact rise from the dead, just as Jesus said they would (16.31). Other details in the vicinity might be interpretable in a related way: for instance, the eighteen-year period for which a disabled woman is bound by Satan might be taken to allude to Caiaphas’s eighteen-year tenure as high priest (13.11–17).

Either way, the rich man’s request for a message to be sent to his brothers depicts the Pharisees’ stubborn-heartedness. They don’t need to be sent a message from the grave; they need to listen to the words of Moses and the Prophets (which repeatedly exhort them to care for the poor) and to those of Jesus, who is alive and well in their midst.

Jesus has come to bring about an Esther-like reversal in Israel--to turn life on its head (or from God’s perspective the right way up). The Pharisees have used God’s word to condemn others and to serve their own ends (e.g., to justify their greed and easy divorces: 16.14, 18). Yet, in and through Jesus’ parables, God’s word exposes their sin, which they refuse to confess. As such, Israel must be judged. There is no alternative. Remarkably, however, rather than allow Israel to perish, Jesus will ultimately take the sadness and the sorrows of his parables on himself so Israel might live again. Like Lazarus, he will be led outside the gate. Like the rich man in his earthly life, he will be clothed in a purple robe at the time of a feast (in mockery of his kingship). Like Haman, he will be hung on a tree. Like the younger brother, he will experience separation from his father (though always remain his son). And, like the rich man in the afterlife, he will thirst. Then will come the reversal of all reversals--the resurrection--, in light of which Jesus now calls us to live.

We could argue about whether the lost sheep, coin, and son(s) should be viewed as one parable or three, but, for ease of reference, we’ll treat them as three for now.

For an alternative, cp. Tomasino, A. J., 2019, ‘Interpreting Esther from the Inside Out: Hermeneutical Implications of the Chiastic Structure of the Book of Esther’ in Journal of Biblical Literature, 138:1 (2019), pp. 101–120.

Also worth mentioning that Lazarus' name means 'God has helped', when Mordecai tells Esther that help will come from another place in 4:14?