Quite a few people in the Bible have two different names. A nice example can be found in Genesis 35.16–18, where the birth of Benjamin is described. Rachel calls her son ‘Ben-Oni’ (בֶּן־אוֹנִי), which means ‘Son of Travail’, while Jacob calls him ‘Benjamin’ (בִּנְיָמִין), which means ‘Son of my Right Hand’.

Benjamin’s two names make a fairly typical pair. When people have two names, one tends to describes their appearance at the time of their birth or a particular feature of their birth (in Benjamin’s case the pain it entailed), while the other describes their parents/guardians’ aspirations for them.

Benjamin would thus seem to have been named ‘Son of my Right Hand’ because Jacob hoped he would (unlike Joseph) remain at his right hand and become the recipient/inheritor of God’s promise to Abraham.1 Or least he may have been.

Whatever Jacob meant to convey by means of Benjamin’s name, however, other people in Scripture have similar name-pairs. For instance, Solomon has two names—Solomon and Jedidiah (II Sam. 12.25)—, one of which is a ‘birth-name’ and the other of which is more aspirational. Solomon (שְׁלֹמֹה) means ‘Compensation’ (or similar) because Solomon’s birth compensated David for the loss of his first child with Bathsheba, while Jedidiah (יְדִידְיָה) means ‘Beloved of Yahweh’ because Nathan hoped Solomon would be especially beloved of God (which he was).

Similarly, the king Jehoiachin has two names—Shallum and Jehoiachin (compare I Chr. 3.15 with the events of II Kgs. 23–24). The birth-name Shallum (שַׁלּוּם) has the same root as Solomon: it was presumably assigned to him because his life compensated/consoled his family after the loss of a loved one. Meanwhile, the name Jehoiachin (יְהוֹיָכִין) means ‘Yahweh has established him’, and was presumably assigned to Jehoiachin upon his accession to the throne.

All well and good, one might say. But what about Sargon II’s name(s)?

Well, Sargon was the last of the three Assyrian kings who brought about Samaria’s downfall. The other two were Tiglath‐pileser III and Shalmaneser V, and, intriguingly, both of these kings bore name-pairs which are similar to those described above.

Tiglath‐pileser’s usual name means ‘My Trust is in the god Ninurta’. The king’s birth-name, however, was Pulu, which means ‘Limestone’. It was probably assigned to him because, as a baby, he had unusually pale skin. Similar ‘complexion names’ are still in use today, and are well represented in the Bible—e.g., Sheshan (שֵׁשָׁן) = ‘Alabaster-Coloured’, Laban (לָבָן) = ‘White’, Puah (פּוּאָה) = ‘Scarlet’, etc.

The situation is much the same with Shalmaneser. Shalmaneser’s usual name means ‘The god Salmanu is foremost’. Shalmaneser also, however, has a birth-name, which is Ululayu and means ‘Born in the Month Ulul’.

We thus come to Sargon II’s name. The name Sargon means ‘The deity established/legitimated him’ (or similar), and is likely to have been adopted by Sargon when he laid claim to the throne. (Sargon says his name was given to him by the gods.)

Sadly, Sargon’s birth-name doesn’t appear in any cuneiform texts we currently possess. But it may be recorded for us in the book of Hosea.

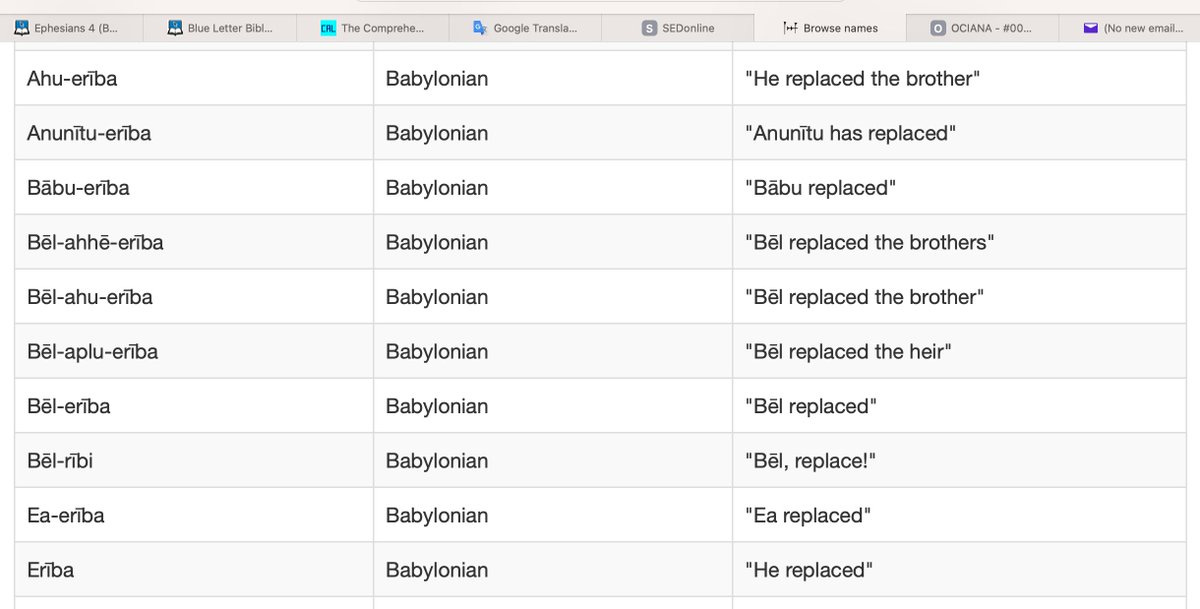

Hosea’s prophecy describes the final downfall of Samaria. In chapter 10, Hosea says Samaria will be destroyed “just as Shalman destroyed Beth-arbel on the day of battle” (Hos. 10.14–15). The final Assyrian king spoken of in Hosea is presumably, therefore, Sargon II, who mentions his conquest of Samaria in his inscriptions. And, curiously, Hosea refers to that king via the somewhat cryptic title “king Jareb” (מֶלֶךְ יָרֵב) (Hos. 5.13, 10.6) (often re-vocalised to read “the great king”), which can plausibly be taken to reflect an Assyrian birth-name formed from the Akkadian verb riabu. The verb riabu means ‘to replace’. As such, it is a near-equivalent of the Hebrew SH-L-M (whence the name Shallum), and it happens to be well attested in Akkadian birth-names. Indeed, the name of Sargon’s successor, Sennacherib, involves the verb riabu, and other names in riabu aren’t hard to find, as a quick search on a database of Neo-Babylonian names reveals.

The book of Hosea may, therefore, record what is an otherwise undocumented name of Sargon II (Eriba).

That can’t be proved, but what can be said about the matter is intriguing: Hosea associates Samaria’s conqueror with the kind of birth-name we’d expect an Assyrian king to have, and he attributes it to a king who’s likely to have had a birth-name we don’t yet know about.

If that analysis of Jacob’s actions is correct, the text of Genesis 35.18 must describe a name which Jacob gave to Benjamin quite a while after Genesis 35.18’s events took place (or, more specifically, after Joseph had been sold into slavery). Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, Genesis 37 could reflect a step back in time—that is to say, Genesis 37’s events could precede Genesis 35’s—, which would explain how Jacob’s ‘mother’ (Rachel) could still have been alive at the time of Genesis 37’s events (per 37.10). If Benjamin had been born by the time Genesis 37’s transpired, Rachel would be dead.

One name is for the persons description in the story. These stories were made so they could remember the details. The other name is the given name on the eight day. Who would name their children puny and weakly? Come on think.