Summary: A garden, a tree, some thorns, some guards, angels, weapons, and flames: Which passage of Scripture do these things bring to mind? Genesis 2–3, right? It’s certainly a valid answer, but it’s not the only one. John’s passion narrative also involves all of these things, and its references to them are highly instructive.

Like all masterpieces, John’s passion narrative works at multiple levels. For a start, it can be read it as a historical narrative and subjected to critical scrutiny. And, when that’s done, it fares pretty well. As Bart Ehrman says, ‘John’s central claims about Jesus as a historical figure—a Jew, with followers, executed on orders of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate—are confirmed by non-Christian sources’.

Furthermore, John’s narrative outlines a plausible sequence of events. Jesus is a threat to Jerusalem’s leaders, who are desperate to get rid of him. But, since they don’t want to execute Jesus themselves (and can’t legally do so anyway), they get Pilate to do their dirty work for them—or at least they try—, at which point complications ensue.

Pilate’s behaviour is plausible too. Pilate can’t work out what Jesus is supposed to have done wrong and is loath to be strung along by the Jews. Consequently, he pronounces Jesus innocent (since, whatever Jesus’ crimes are, he is clearly no threat to Rome), which prompts Jerusalem’s leaders to mobilise ‘the mob’. And so, anxious to avoid civil unrest, Pilate capitulates, and Jesus is led away to be executed.

John’s passion thus makes sense as a historical narrative, and is a highly instructive one. It reveals (among other things) some of the problems with weak leadership, some of the dangers of envy, and the nobility of those who remain true to their convictions (even in the face of death).

Such considerations, however, are only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface of John’s narrative are multiple theological narratives, each of which highlights a different aspect of the significance of what takes place on the cross.

For a start, John’s narrative raises political questions. If Jesus is a king, then what kind of king is he? Where is his kingdom? How does Pilate’s ‘power from above’ fit into it? And how can a kingdom prosper when its king is so ready to serve, not to mention surrender his life?

At the same time, John’s passion is laden with sacrificial imagery. We have a victim bound with cords (like a sacrifice), led into a priestly courtyard (with a fire/altar at its centre!). And, later, we find Jesus surrounded by ritual-related imagery such as wood, scarlet fabric, hyssop (dipped in wine/blood), and fresh water (cp. Leviticus 14), all of which serves to frame Jesus as the culmination of Israel’s sacrifices.

In addition, John’s passion has a legal dimension. Jesus is declared innocent by Jerusalem’s legal authorities, yet is nevertheless treated as a guilty party, which reflects (and in part effects) the theological consequences of Jesus’ death. In death, YHWH’s ‘righteous servant’ is ‘reckoned among the transgressors’ (Isa. 53). A sinless one becomes sin on his people’s behalf (2 Cor. 5).

In what follows, however, I want to consider a different layer of imagery altogether: creation related imagery.

John and Creation

That John’s Gospel contains allusions to creation isn’t hard to see. John’s Gospel opens in darkness, with God accompanied by ‘the Word’, against which backdrop the Spirit hovers above the waters (of baptism), and a greater and a lesser light emerge on the earth (Jesus and John).

John’s passion also contains allusions to creation. A garden, thorns, guards, flames, a source of life drawn forth from a man’s side: so the list goes on.

John’s use of these images is often dealt with summarily, as if John simply wanted to allude to the general notion of (re)creation (because a new age was about to begin), but didn’t have much else to tell us. John’s use of creationary imagery, however, is careful and precise. It can be analysed in terms of three main categories.

(1). Context-definers

John’s narrative involves various details/images which define a context in light of which its events are to be interpreted. Unlike the Synoptics’, John’s passion is set within a garden—or, to be more precise, it’s bookended by references to gardens. It opens in the garden near the river Kidron, and closes in the garden in which Jesus’ tomb is located. Its events thus (symbolically) unfold within the context of a garden.

Meanwhile, whereas the Synoptics have the skies grow dark at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion, John enshrouds his entire passion narrative in darkness. Its events are initiated by a man who heads out into the night (to betray his master); it opens in darkness when Jesus is arrested in the darkness of the Kidron valley (‘Kidron’ means ‘darkness’); and it concludes at nightfall as Nicodemus—who first approached Jesus at night (cp. 19.39)—carries Jesus’ body away.

These details are significant. For John, Jesus’ crucifixion is dark and decreational. As John’s passion week comes to a close, a primordial darkness envelops the land (just as the floodwaters enveloped the pre-flood world).1 Mercifully, however, John’s Gospel doesn’t end in darkness. The darkness of the crucifixion is not a darkness which will overcome the light; it is a darkness which stands at the cusp of a new dawn, pregnant with hope. And, in ch. 20, that hope is realised. In and through Jesus’ resurrection (the Son-rise), the darkness is dispelled. The land of Israel emerges from the floodwaters. A new day dawns.

(2). Sequential Imagery

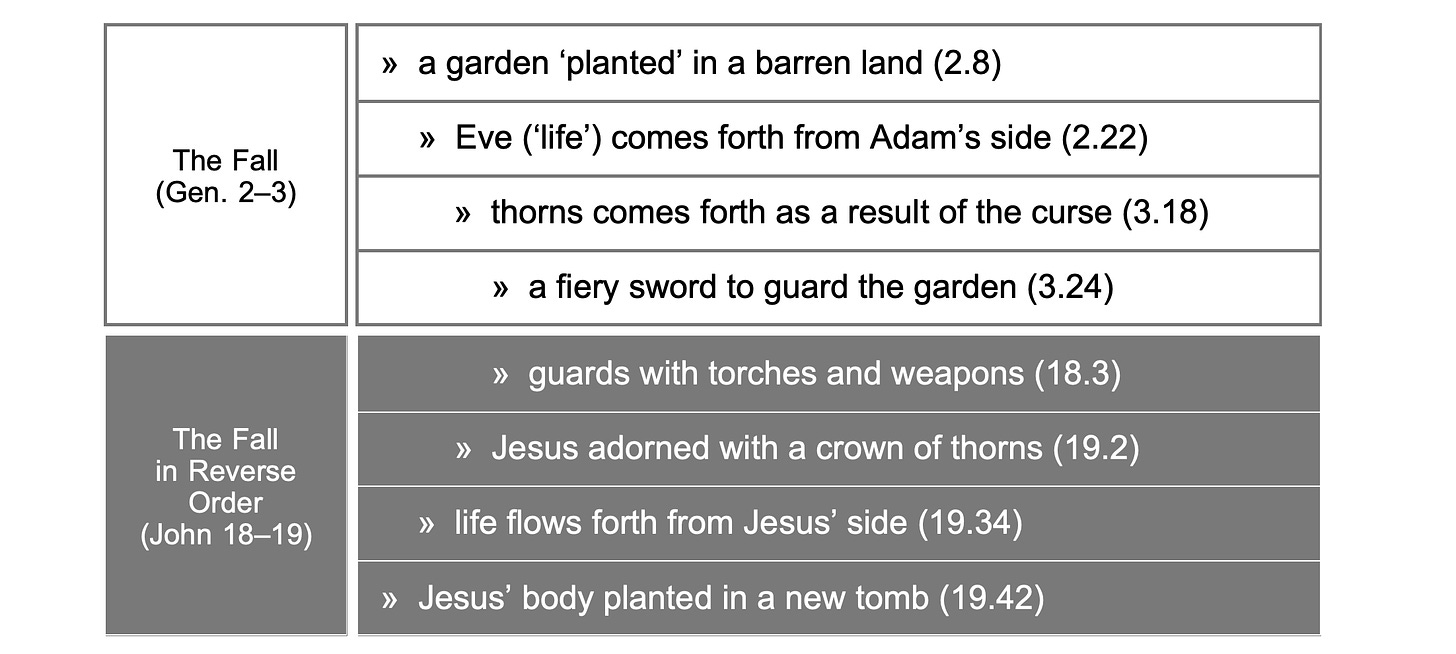

John’s narrative also incorporates a sequence of images which depict a reversal of man’s fall. It begins with (allusions to) the effects of Adam’s sin (Genesis 3), rewinds through the cultivation of Eden (Genesis 2b), and ends in a barren garden (Genesis 2a)2—a direction of travel illustrated in the table below:

As we move through the text of Genesis 2–3, we read about a barren garden, the creation of Eve (from Adam’s side), a thorn-cursed creation, and a fiery sword-bearer (who blocks the way to the tree of life). Then, as we move through the text of John 18–19, we encounter (allusions to) the same events, but arranged in reverse order. Symbolically, therefore, Jesus undoes Adam’s fall. First of all, he approaches the garden’s guards (equipped with torches and weapons), who fall backwards as he announces his identity (‘I am the one!’). (The way to the tree of life will soon be reopened.) Next, Jesus is brought before Pilate’s judgment seat, where he is crowned with thorns, i.e., where he takes the responsibility for Adam’s sin. Thereafter, a spear is thrust into Jesus’ side,3 from which the water of life flows forth. (‘Eve’ means ‘life’.) And, finally, just as Eden is ‘planted’ in a land in which no-one has previously laboured, so Jesus’ body/seed is planted in a tomb in which no-one has previously lain. Like Adam, Jesus returns to the ground. John’s narrative thus takes us back to a pre-fall world—to a time prior to man’s transgression, to a place (the garden) prior to man’s exile, and to a state prior to creation’s curse, which it does by means of distinctly Johannine imagery.

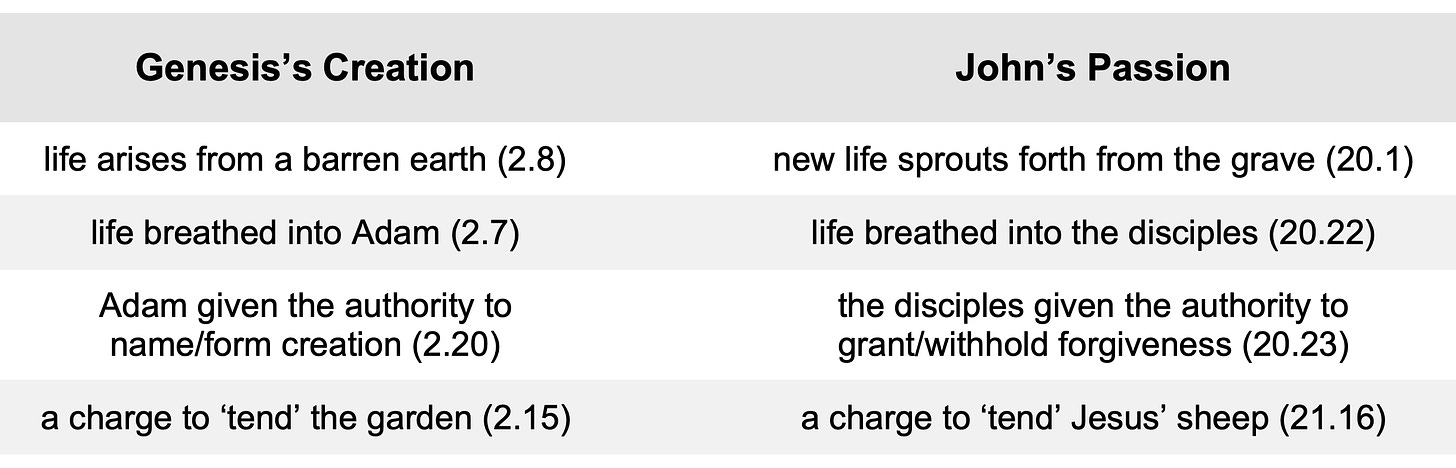

John’s story, however, is far from over. Just as the darkness of the crucifixion is not a darkness which overcomes the light (but anticipates its arrival), so the barrenness of John 19’s garden is not the barrenness of infertility; it is a barrenness of an unformed world which anticipates new life. Buried within it is the body of Jesus—a grain of wheat which has died and fallen into the ground. Hence, in John 20, on the basis of Jesus’ resurrection, Jesus assigns his disciples a new Adamic commission, which will continue to undo the effects of Adam’s fall.

(3). Juxtapositions

John’s narrative also involves images which portray Jesus’ actions as those of a man who triumphs where Adam fell. These images extend the notion of curse-reversal, but with their spotlight on Jesus’ obedience.

Let’s spell out the relevant contrasts in more detail. Consider for a start the events of the garden next to the Kidron valley. Whereas the first Adam incriminates (‘The woman gave it to me!’), the last Adam protects (‘Let these men go!’). Whereas the first Adam hides in the garden, the last Adam puts himself in the cross hairs. And, whereas the first Adam is provided with a helper, the last Adam is abandoned; like the Levitical high priest, he must do his work alone.

Next, consider the events of Jesus’ trial. Whereas the first man fails in his task and ‘becomes like the gods’, the God made man triumphs. Whereas the first Adam is crowned with glory and honour, which he later exchanges for thorns, the last Adam is crowned with thorns, to be exchanged for a crown of glory. And, whereas the first Adam’s reference to a ‘woman’ is an accusation, the last Adam’s ensures his mother’s safety. (‘Woman, behold your son!’)

Finally, consider Jesus’ death. Whereas Adam takes his first breath in a garden, Jesus breathes his last in a garden. Whereas Adam freely eats from a tree, Jesus is compelled to drink from a divinely appointed cup. And, whereas the first Adam’s disobedience brings death on his descendants, the last Adam’s obedience brings life to his people. Per Caiaphas’s prophecy, ‘one man dies for the nation’.

A final reflection

John’s passion narrative involves an array of creation-related images. These images are not randomly strewn throughout the text, and cannot (or at least should not) simply be slotted into our favourite schema. They have been carefully arranged so as to depict the reversal of Adam’s fall, courtesy of Jesus’ obedience. And, by means of their backdrop of primordial darkness, they situate Jesus’ death at the very dawn of time (cp. ‘the lamb slain from the foundation of the world’: Rev. 13.8?), which is highly significant. Just as the effects of the fall have rippled outwards until all creation has felt their force, so too will the effects of Jesus’ death, until the whole earth has been filled with the knowledge of God.

Also worthy of note is John’s artistry. John’s use of imagery is not contrived, nor is it blatant. Rather, John weaves a range of different images into the fabric of a credible and coherent historical narrative, whose various sub-themes simultaneously come to their climax in the death of Christ at the culmination of the greatest story ever told.

Consider how the post-flood story is an act of (re)creation. A wind blows across the earth, the waters recede from the land, life begins to sprout forth, birds once again inhabit the land, and so on.

Cp. Nicholas Schaser’s excellent paper ‘Inverting Eden: The Reversal of Genesis 1–3 in John’s Passion’ in Word & World, Vol. 40:3 (Summer 2020), pp. 263–270.

The mention of Jesus’ side (πλευρά) is said to be the ‘fulfilment’ of Scripture, which, among other things, exploits the resonance between the words πλευρά = ‘side’ and πληρόω = ‘fulfill’.

Hello! I absolutely love this article. Although, I am a little lost in regards to the comment about John starting in a garden. I can easily see the garden at the end, but I am having a harder time seeing it at the beginning. Could you possibly share some additional information about this with me?

Amazing to consider how deep the interconnection of the scriptures go. Quite the rabbit hole you have explored here. Thank you for sharing you insights!