Belshazzar’s Riddle (Part I)

When I consider the work of your hands...

Summary: Daniel’s solution to the riddle inscribed on Belshazzar’s wall (viz. MNHMNHTKLPRSYN) is more involved than it first seems. Daniel decomposes the riddle into three triliteral nouns (meneh, tekel, and peres), which form the basis of his (highly elegant) solution to the riddle. But why is ‘decomposition’ necessary? If God’s message to Belshazzar could have been summed up in three triliteral nouns, why didn’t God simply write the consonants MNHTKLPRS on Belshazzar’s wall? (Riddles are generally known for their succinctness.) Why do we instead find two occurrences of the word meneh in Belshazzar’s riddle yet only one in Daniel’s solution? And parsin in the riddle yet peres in the solution? And why are different weights mentioned anyway? Typically, such issues are dismissed as products of textual corruption and/or vestiges of earlier versions of Daniel’s story. A consideration of our text’s lexical and numerical properties, however, explains the Masoretic Text as we have it today, and does so in an exegetically fruitful way.

For a pdf version of the present note (with bibliographic details, etc.), see https://www.academia.edu/44211586/. Otherwise, please scroll away!

Numbers

The text of Daniel 5 is patterned around a whole array of threefold groups and structures. It consists of three paragraphs and thirty verses. It contains three notable triads, namely:

Daniel’s trio of attributes (‘light, insight, and wisdom’),

Daniel’s threefold ability (‘the ability to interpret dreams, explain riddles, and solve problems’), and

Belshazzar’s threefold reward (‘to be clothed in purple, adorned with a gold chain, and made the third most powerful man in the kingdom’), which, of course, is mentioned three times.

And the events of Daniel 5 come to their climax with a nine-fold condemnation of Belshazzar’s idolatry,

…at which point Daniel presents his solution to Belshazzar’s riddle, which is similarly threefold in nature. It’s predicated on a nine-syllable utterance (‘Meneh Meneh, Tekel, and Parsin’), which Daniel distils into a 3 x 3 matrix of characters (below),

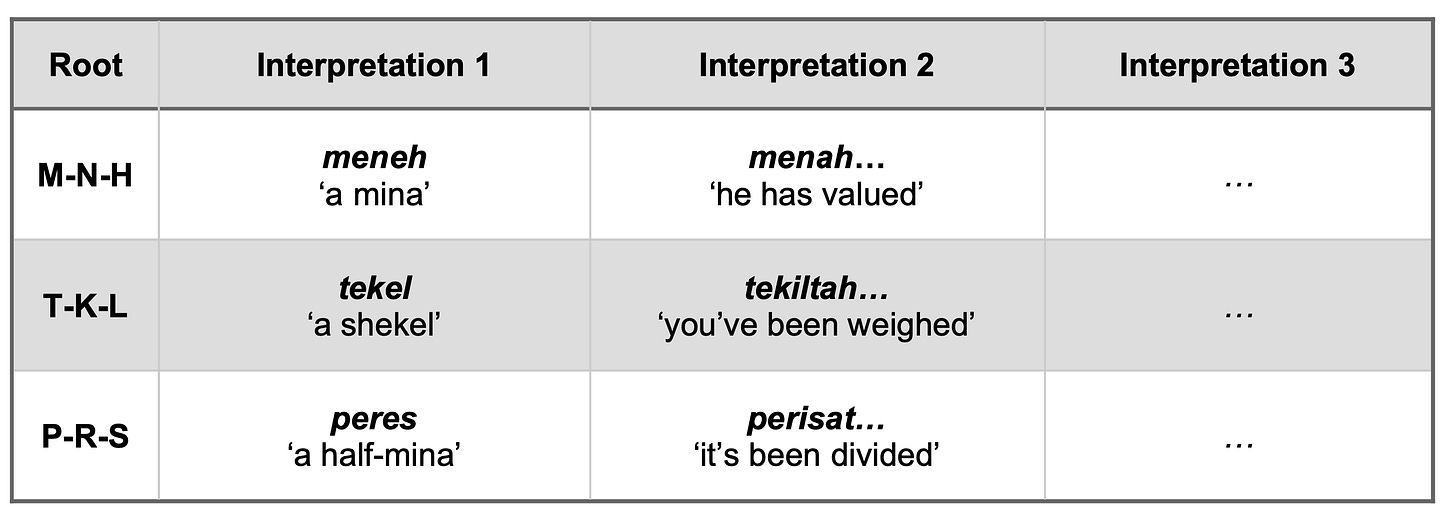

…from which Daniel generates a second 3 x 3 matrix, where he interprets each of the triliteral ‘roots’ of meneh, tekel, and peres in three different ways. From the root M-N-H, Daniel generates the words meneh, menah, and manniyah; from T-K-L, the words tekel, tekiltah, and kalletah; and from P-R-S, the words peres, perisat, and paras, per the matrix below,

…which Daniel puts together and expands to yield his solution (and hence his message to Belshazzar), as follows:

The details of these three levels of interpretation will be addressed later. First, however, let’s briefly rewind and consider the broader context of Belshazzar’s riddle.

Belshazzar’s feast

At the outset of Daniel 5, Belshazzar throws a party for the thousand most important people in Babylon. As the party warms up, Belshazzar wonders if his wine might taste better drunk from YHWH’s temple vessels, which he orders to be brought out from the treasury. Belshazzar also, apparently, orders God’s lampstand to be brought out (5.5).

Suffice it to say, Belshazzar is gravely mistaken. YHWH’s vessels will not improve the taste of his wine. What Belshazzar has begun to drink from is the cup of YHWH’s wrath (cp. Jer. 25). And, as he does so, right on cue, YHWH’s hand appears out of thin air and inscribes a series of characters on the palace wall.

Much to his dismay, Belshazzar is unable to read what YHWH has written, let alone ‘interpret’ it, which makes YHWH’s inscription all the more ominous. And Belshazzar’s wise men are unable to furnish him with any help. (Significantly, their inadequacy will prove to be their third and final failure in the book of Daniel.)

The message on Belshazzar’s wall is clearly cryptic/encoded in some way, since Belshazzar and his men can’t read it. Whether it’s written in cuneiform, logograms, or an alphabetic script isn’t stated. In 5.25, however, Daniel is said to read the message out in the Aramaic language, which was normally written alphabetically (i.e., without vowels).

For now, then, we can think of the inscription on Belshazzar’s wall in terms of the string of consonants below.

MNHMNHTKLPRSYN

Daniel’s interpretation of these characters proceeds as follows. First of all, Daniel identifies three triliteral roots in the characters: M-N-H, T-K-L, and P-R-S. By the insertion of vowels, Daniel turns these roots into known Aramaic words; specifically, he generates the words meneh (5.26), tekel (5.27), and parsin, which is the plural of peres (5.28). Daniel thus interprets the consonants before him as a series of nouns, which are their ‘face-value’ sense—their peshat, as it were.

So, what exactly do these three nouns mean? In essence, they designate weights. The word meneh signifies a mina, i.e., sixty shekels. The word tekel is an Aramaic pronunciation of the word ‘shekel’. And the word peres refers to half of a given weight/quantity. It would most naturally have been understood as a mina.

The first step of Daniel’s interpretation of the characters on the wall is, therefore, clear enough: Daniel divides the consonants into groups of three, and interprets them as references to weights (5.25), as shown below:

Level 2

The second step/column in Daniel’s interpretation of the characters is also fairly clear. Daniel interprets each group of consonants not as a noun, but as a verb. He converts meneh into menah (a G-stem conjugation of M-N-H = ‘to weigh/value’) and expands menah to menah elaha malchutach = ‘God has valued your kingdom’. He converts tekel into tekiltah (a G-stem conjugation of T-K-L = ‘to weigh’) and expands tekiltah into tekiltah ve-mozanyah = ‘you’ve been weighed/valued on the balances’. And he converts peres to perisat (a G-stem conjugation of P-R-S = ‘to divvy up, distribute’) and expands perisat to perisat malchutach vi-hivat lemaday-u-faras, as shown below. (A G-stem conjugation can roughly be thought of as a verb’s most ‘basic’ form.)

Daniel’s third and final step/level is then to reinvent these consonants more creatively/expansively (details to follow shortly), all of which means we can schematise Daniel’s solution to the king’s riddle as a 3 x 3 grid, where Column 1 is a weight, Column 2 is a sentence derived from the ‘root verb’ of the relevant weight, and Column 3 is a reinvention of the root verb:

Level 3

We thus come to Level 3 of Daniel’s interpretation, which requires us to take a brief step back and consider the notion of ‘signs’ in the Mesopotamian world. The appearance of God’s hand midway through Belshazzar’s feast would (not unreasonably) have been seen as a ‘sign’ issued at the gods’ initiative—in the Babylonians’ terms, an ‘unprovoked sign’. And, from the Babylonians’ perspective, it was vital for signs to be interpreted (alt. ‘divined’). To interpret a sign, however, wasn’t merely to explain/exegete its content. Uninterpreted signs were sources of mystery and unbridled power which needed to be ‘defused’ by an interpreter. Ideally, of course, the sign would be interpreted favourably (in which case its interpretation would be seen as performative), but an unfavourable interpretation was also welcome, since it at least unveiled/defused the mystery inherent in the sign. More importantly, it gave the Babylonians an opportunity to avert the disaster it anticipated. A sign with an unfavourable interpretation was more an alert than anything else. (‘Tread carefully!’)

As for the means by which such signs were interpreted, a variety of techniques could be employed. When the sign-to-be-interpreted was an inscription, however, like the consonants MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN, wordplay was the most natural option. Such wordplay was typically based on lexical (re)analysis and homonyms. For instance, one omen text says in relation to a man who’s dreamt about a ‘raven’ (aribu), ‘He’ll acquire much income (irbu)’, while another says in relation to a man who’s dreamt about ‘flesh’ (sheru), ‘He’ll acquire riches (sharu)’. Similar examples can be found in the Biblical narrative, e.g., in Amos 8.2, where a vision of a basket of kayitz = ‘summer fruit’ is interpreted as a sign of ketz = ‘the end’. And, as we’ve seen, Daniel clearly utilises wordplay to yield the second level of his interpretation. (For instance, he reads the consonants MNH as menah instead of meneh.) Daniel also makes use of the same technique (in a more expansive way) in the third level of his interpretation, which we’ll now consider. Recall Daniel’s interpretation:

Or, for those who are happy to work directly from the Masoretic Text,

Each Level 3 interpretation is based on a reinvention of each line’s root, which Daniel would presumably have explained to his (stunned) audience as he announced his solution (in which case the text of 5.26–28 should be seen as a summary of a longer address). In Line 1, Daniel ‘reads’ the consonants MNH as manniyah (מַנִּיָהּ), i.e., ‘He has assigned it to you’ (5.26c). In Line 2, Daniel rearranges the consonants TKL to read kalleta (קַלְּתָּ), i.e., ‘You’re too light!’ (5.27c). And, in Line 3, Daniel reads PRS as paras (פָּרַס) (‘Persia’) and then combines paras with perisat (‘it’s been allocated’) to yield the statement ‘Your kingdom has been allocated to Medo-Persia’ (5.28c).

A word or two on my translation of 5.25–28. I take the first occurrence of the word meneh (מְנֵא) in 5.25 to be a passive participle (i.e., ‘has been weighed’). I therefore take Daniel’s initial statement of the riddle to have the sense, ‘A mina has been put on the balances, and a shekel and two peres-weights alongside it’. In other words, three quantities have been put on the balances and their (relative) weights have been assessed. Daniel’s interpretation of the riddle in 5.26–28 then flows forth from and expands on his initial statement of it in 5.25. Specifically, Daniel’s interpretation explains what a mina, shekel, and half-mina designate and how they relate to one another.

In Line 1, I take M-N-H to have the sense ‘to weigh/value’ (as I also do in 5.25). I hence take Line 1 to have the sense, ‘God has valued your kingdom at a mina and entrusted it to you’. Of course, a mina is primarily a weight rather than a value. ‘A mina of what?’, one might therefore ask.

In light of Daniel 2, ‘a mina of gold’ seems as reasonable a guess as any, but it ultimately makes little difference to our exegesis, since our text concerns the relative values of a mina, shekel, and half-mina (of a given substance). As a result of the exile, Babylon is the home of God’s people, and whoever governs it must do so in accord with its newly-acquired value.

In Line 2 (5.27), I take the sense of Daniel’s statement to be, ‘You, O Belshazzar, a mere shekel, have been weighed in the balances (tekiltah) and found to be insufficient (chassir), i.e., too light!’. Given his role, the king of Babylon has to be a man of weight/dignity, which Belshazzar clearly isn’t. While Nebuchadnezzar acknowledged God’s glory, Belshazzar has refused to do so (5.20–23). Like his wise men, he’s not up to his job.

In Line 3 (5.28), I take the consonants P-R-S to have the sense ‘to divvy up, distribute’, which resonates with 5.25’s mention of two half-minas (parsin). I’ve therefore rendered 5.28 as, ‘Your kingdom has been broken in two and has been allocated to Medo-Persia’—a statement which has both a literal aspect (insofar as Medo-Persia has two prongs/arms, which makes it an appropriate steward for a two-peres kingdom) and a metaphorical aspect (insofar as Belshazzar’s hold over the ANE has been broken in two).

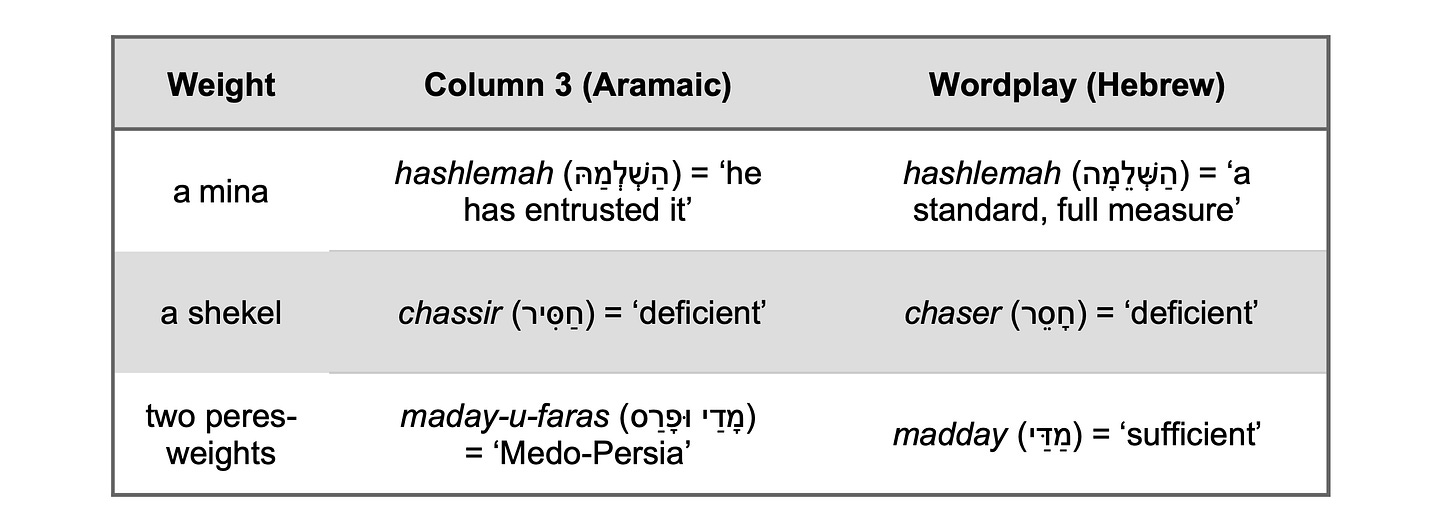

The flow and logic of 5.26–28’s events is thus as follows. God has determined ‘a mina of the land/kingdom of Babylon’, i.e., a standard (like the metre bar in Paris); that is to say, he’s determined the worth of Babylon and, by implication, the measure of the man who should govern it. Belshazzar, however, doesn’t measure up to God’s standards. He’s a lightweight (cp. 5.22–23). Consequently, his kingdom will be divvied up and (re)distributed to a more suitable empire—a twofold empire (Medo-Persia), an empire of sufficient weight to carry God’s plans forward. Put in terms of ch. 2’s vision, the golden head will give way to the arms of silver—a fact which is subtly reflected in Daniel’s statement to Belshazzar in 5.23. When Belshazzar’s idolatry is first described, Babylon’s gods are listed in the order ‘gold, silver, bronze, iron’, but, when he condemns Belshazzar’s idolatry, Daniel moves ‘silver’ to the top of the list (‘silver, gold, bronze, iron’: 5.23). The empire of silver (Medo-Persia) is on its way up, while the empire of gold (Babylon) is on its way down. The weights spelt out by the consonants MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN aren’t, therefore, arbitrarily chosen. Each weight represents a specific king. The mina represents Nebuchadnezzar, the shekel Belshazzar, and the two peres-weights Darius and Cyrus. And, curiously, by means of further wordplay, the final column of Daniel’s interpretation can be converted into a series of (Hebrew) terms which allude to these three weights:

For Part II, cp. https://jamesbejon.substack.com/p/belshazzars-riddle-part-ii.